Last week’s theme for James and I was Dieback. During the week, I have been wondering how many people we know, or who read our blog, truly know what “Dieback” is, and what the impact is on our environment. Here’s some excerpts from the Dieback Working Group web site that illustrate this “biological bulldozer”*.

Phytophthora Dieback refers to the deadly introduced plant disease caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi (… meaning plant destroyer in Greek). There are over 140 species of Phytophthora, but the species that causes the most severe and widespread damage to native plants in Western Australia is P. cinnamomi.

When Phytophthora Dieback spreads to bushland, it kills many susceptible plants, resulting in a permanent decline in the diversity of the bushland. It can also change the composition of the bushland by increasing the number of grasses and reducing the number of shrubs. Native animals that rely on susceptible plants for survival are reduced in numbers or are eliminated from sites infested by Phytophthora Dieback.

An example of the impact of dieback

Over 40% of native WA plant species are susceptible to Phytophthora Dieback. Over 50% of the WA’s rare or endangered flora species are susceptible. Many of these plants are only found in the Southwest Australia Ecoregion.

Human activity (…) causes the most significant, rapid and widespread distribution of this pathogen. Dieback could be in your garden killing your roses, it could be in the bush around your holiday home near Dunsborough or a threat to your flower farm near Walpole. Phytophthora Dieback could also be at your favourite picnic spot near the Mundaring Weir or in the bushland near your favourite fishing spot near Bremer Bay.

This introduced disease is a massive threat to the ecosystems of the south-west of Western Australia (where I grew up) and I’m proud that we have been able to play a role in helping the scientists and programs involved muster their forces against it.

So, our week of Dieback started on Monday, when we gave a small group of New Zealand scientists that was led by Nari Williams from SCION Research an overview of our historical work in this area. This was a nice retrospective for me and it really set the scene for our week well. I started the presentation (as usual) with a PowerPoint presentation to set the scene:

My short slideshow on our Dieback projects

We finished the workshop with a pretty quick demonstration of the Dieback Information Delivery and Management System (DIDMS), which is the system that manages all this Dieback information (and is based on our GRID product). The feedback at the time was how easy this was to use, and this was echoed again later in the week. It was great to have the ability to show off these projects – some of which were huge chunks of work for us and were things that we are still very proud of.

Fast forward a few days, and James is out at a car wash, getting his Green Card. While we don’t do a lot of field work directly ourselves, I am a firm believer that we need to understand how our clients work, and what our solutions can do to support this. So while James was out doing the training, he was also picking up other ideas about how we can support this industry, and learning more about how to make sure our own work doesn’t spread it further. He’ll be sharing his insights with our team at our next Friday drinks session, too.

I’ll let James summarise this bit:

Green Card training was developed (by the Dieback Working Group and the Department of Parks and Wildlife among others) to provide recipients with the knowledge required to implement Phytophthora Dieback hygiene principles on the ground. The hope is that this type of training will soon become a national standard for individuals or organisations working in Phytophthora Dieback susceptible or infested areas.The training was exceptionally well presented by Kat Sambrooks and comprised the following key information and messages:

- An interesting summary of Phytophthora spp. biology,

- Current research into the nature of the pathogen both in terms of its impact and vectors of spread,

- Common misconceptions (for example it used to be called Jarrah Dieback but in actual fact around 40% of native plants in the southwest of WA are susceptible – not just Jarrah!),

- Current management principles,

- Current treatment options (not many and not very effective – far better off containing and protecting as much as we can!),

- Legislative tools for management,

- Field identification, and

- Hands-on principles of hygiene.

Clockwise from top left – one foot print is all it takes, class in session, 4WD wash down, identifying in the field

It is sobering to contemplate the impact the pathogen has already had on our unique flora (and fauna indirectly) with over 2200 species of native plants already affected in WA – and many of these key species that significantly alter the structure of an ecosystem with their loss.

It is also extremely worrying when you consider how easily the pathogen can spread. All it takes is a little soil on your boot or those hard to reach places on your vehicles mud guard and whole ecosystems can be taken out (at least how we once new them).

This is why the Green Card training provided by the Dieback Working Group is absolutely essential for anyone doing any kind of field work in the southwest including educational and research bodies, councils, environmental consultants, utility companies, forestry, landcare groups and the list goes on.

A good tip – clean, clean, clean (before and after) field work, and abstain from field work when it’s wet!

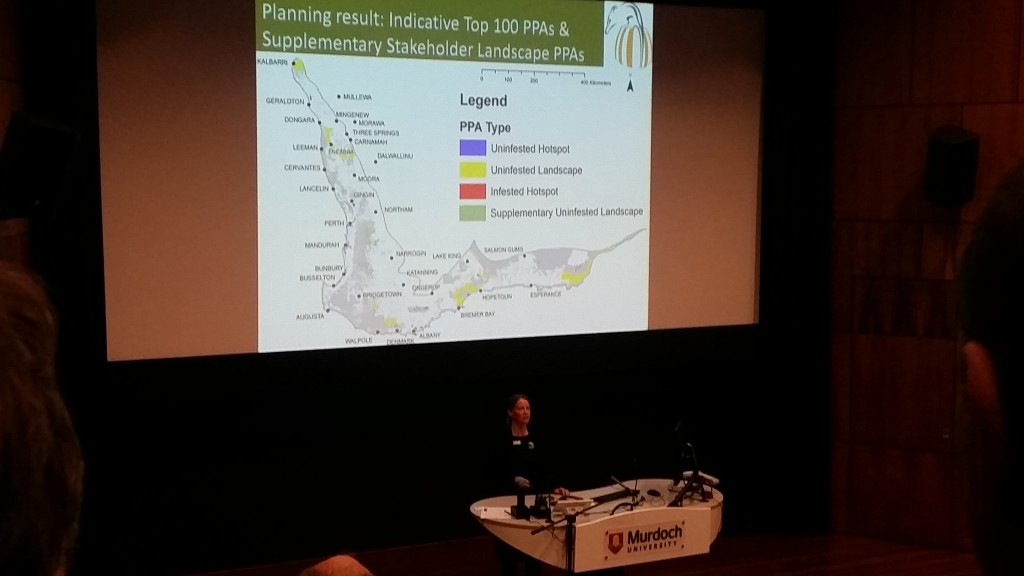

On Friday, I rejoined James to go to Murdoch University for the Dieback Information Group conference. The conference is always a good day where we can really get our heads into the ways in which Dieback is managed and treated. I realised just how big a part we’ve played in Dieback when Elissa started her presentation, a retrospective of Project Dieback. The Statewide Management and Investment Framework (SMIF) got a big mention, as the spatial analysis we did in this project has set the scene for the ongoing areas of priority management by identifying over 100 Priority Protection Areas (PPAs).

Elissa Forbes (from Project Dieback and South Coast NRM) presenting on the PPAs

These PPAs are areas that were deemed highly valuable (from an ecological standpoint) and need to be protected (or, in the case of areas that are already infested, treated where possible). As part of Project Dieback, the team then did on-ground assessments of around 50 of these PPAs, and did a range of upgrades to signage, control, containment and the like. Elissa then finished up her presentation with a mention of DIDMS and a live demonstration (always nerve wracking) of the Public Dieback map that is driven by data held in DIDMS, again work that we have had a long involvement in.

At the conference, there were also a range of other presentations which had three main themes for me: research, on-ground work and communications.

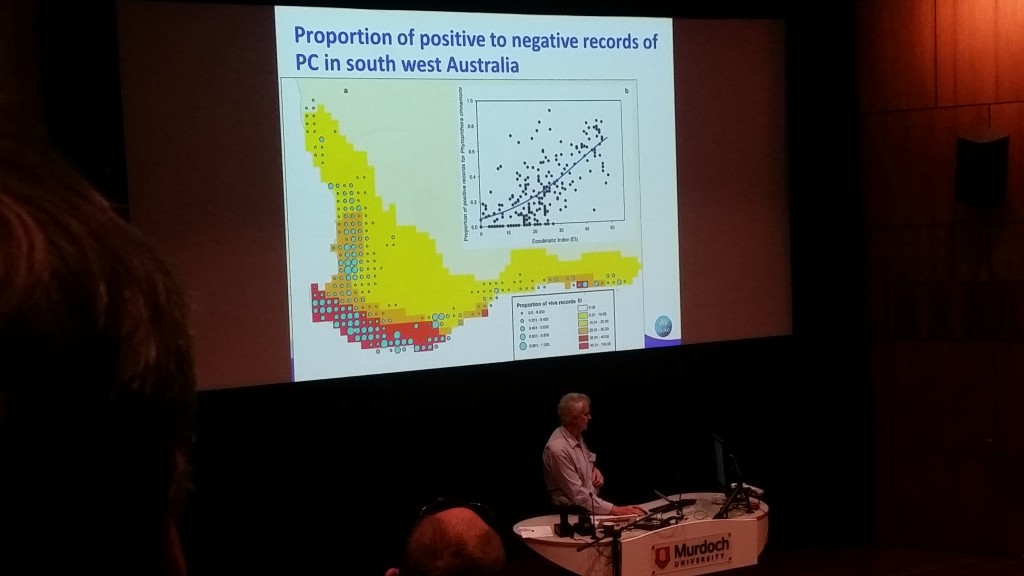

In terms of the the science and research underway (including from our NZ colleagues), which had a range of really positive messages about some of the research that is underway. The advances in genetic research (and “medicalomics”) really seems to be opening up some new avenues for treatment and eradication. Some of the research into distribution (such as John Scott’s talk) also showed just how far we’ve still got to go in terms of the basic understanding of this disease.

John Scott (CSIRO) presenting some of his data on distribution of Dieback

Applying that research – and doing more – in the field was another theme in the presentations. It was really interesting to see some of the results of field trials (with a shudder echoing through the audience at the thought of deliberately infesting areas with Dieback) indicating there is some light on the horizon for controlling Dieback in the field – even seeing that there are potential avenues for microfauna (like nematodes) to predate on the Dieback fungus.

Similarly, controlling Dieback is not just about lab research, or on ground trials and it was great to have a few presentations that focussed on communications. Research and on ground work isn’t going to make on ounce of difference if hygiene measures (like the stuff James learned in his Green Card course) aren’t followed, and Dieback is unknowingly spread across the State. Communicating the messages is something that still needs a lot of work – something that I’m personally quite interested in.

So, what’s next?

Happily, Project Dieback and the Dieback Working Group both received grants from the State Natural Resource Management Program (through the Community Capability Grant program) to start this work. We are supporting the Project Dieback project through their “Increasing community capability to strategically manage Phytophthora Dieback in WA” grant – where we’ll be helping develop the community around Dieback in terms of training groups in using DIDMS and associated tools in Quantum GIS; we’ll also be looking at other ways we can help support the community and these tools into the future.

So, all we have to do (and I know this isn’t a small thing) is coordinate all the good work on research, on-ground work and communications that we saw at the conference. The stage is set for one hell of a fightback, and we’re looking forward to playing our part.

Piers

P.S. Oh, again – keep in touch with comments below, or start a conversation with us via Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn.

* This was an edited excerpt from https://www.dwg.org.au/what-is-phytophthora-dieback, with my own emphasis.

Comments are closed.