A month or so ago, Piers, Aaron and myself attended the launch of the South Coast NRM Dieback Information and Data Management System in Albany and we also took the opportunity to perform some field testing of the mobile applications we have been developing for the Atlas of Living Australia. One aspect of this testing was some analysis of the GPS hardware in modern consumer grade phones and tablet PCs.

There seems to be an expectation these days that the in built-in GPS in mobile phones and tablet PCs are not accurate and aren’t good enough for any serious location work. To be honest, some of our early testing was supporting this theory – however as we have been using the devices more and learning how to interface with them some interesting results are starting to emerge.

On our trip I took along a commercial grade dedicated GPS (Garmin GPSMap 60csx) with the aim of comparing the tracks between it and my trusty Samsung Galaxy Tab running the BDRS mobile tool. As you may have read from a previous blog article, we logged some 306 records over the two day road trip and this provided an ideal dataset to compare with the track produced by the Garmin. The idea was simple, log tracks with both units and compare the difference. You might recognise this photo from the earler article. What you might not have noticed is the second GPS sitting on the dashboard there…

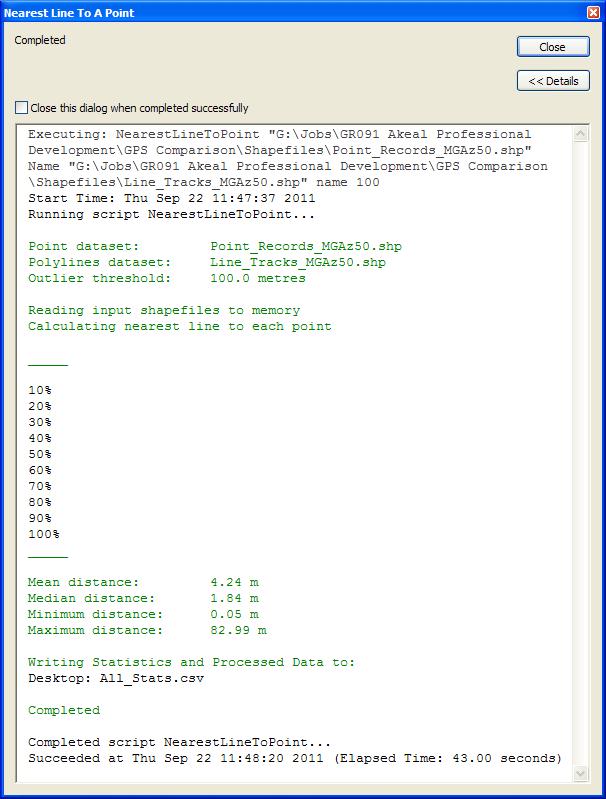

The results were astounding! Not only was the tablet PC’s GPS in the ballpark of the dedicated GPS, the point data was mostly bang on. This was backed up by the spatial analysis done by Akeal of the Gaia Spatial team. Akeal was able to knock up an ESRI ArcGIS Python plugin in no time to perform a spatial analysis of the data by calculating the distance between the points coming out of the BDRS mobile tool and the Garmin GPX track log.

As you can see from the plotted points above, most of the GPS points logged from the tablet (dots) are right on the track produced by the dedicated GPS (yellow line). In fact, the detailed analysis shows that the median difference between the two devices was a mere 1.8 metres – well within normal GPS drift zones.

Whilst the mean difference is somewhat higher (around 4 metres), this can be explained by outlying points where the tablet has lost GPS reception due to standby mode, or where we haven’t logged data using the Garmin.

All up, I was very impressed at the quality of the GPS feed coming out of the Samsung Tablet and feel that it is more than accurate enough for most citizen science applications. We will be no doubt testing other devices in the near future, so stay tuned for more updates on the topic, but in the meantime, if anyone tells you you can’t get accurate GPS data from smartphones and tablets, they’re simply wrong!

AJ

Comments are closed.