As part of our work in the field of Citizen Science we attempt to keep abreast of new initiatives; two recent advancements have caught our attention, and they address two of the main barriers to successful science projects – the ‘price of entry’ and the ‘longevity of data’.

The ‘price of entry’ for establishing a successful citizen science project seems at first glance to be small. After all, a single scientist with an army of volunteers can get a long way with a well-designed project, and the primary cost is time, some notebooks and computer skills. Engagement is key, as we’ve discussed many times previously.

Many citizen science project leaders come to us looking for the next step – to streamline data flow, improve data accuracy, or extend their volunteer range (in both age and location). A smartphone app is usually what they are looking for. If they have little funding they must usually resort to using existing freely-available apps that meet enough of their data needs; or cajole a mate, colleague or their own offspring to have a crack at developing what they need.

This approach can solve the data capture or front-end process. but the back-end data repository is often neglected, and getting the data out can be difficult and time-consuming. For this part of the market, where good science is required to investigate real-world issues in conservation (traditionally an area that receives little funding anyway), there a couple of new initiatives that might be of great use to Citizen Science.

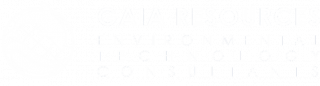

The first is Glide – a new open platform for developing simple yet flexible web apps – without code. From a Google Sheet, Glide assembles an attractive, data-driven app that can be customised and simply shared. Updates to the design or spreadsheet flow on to the user without fuss. Launched in February, this no-code platform makes defining custom fields with controlled vocabularies, automated fields, integrated image uploads and good design available to anyone who can wrangle a spreadsheet.

All submitted data is stored in a Google Sheet, which also makes data management pretty easy too. What Glide apps can’t currently do is associate a geocode with each record, due to privacy concerns. Their work-around is to allow you to enter an address, which is then geo-located and used to represent the observation on a map. The geocode itself is not stored in your sheet, but much work is going into developing the platform and this limitation may soon change.

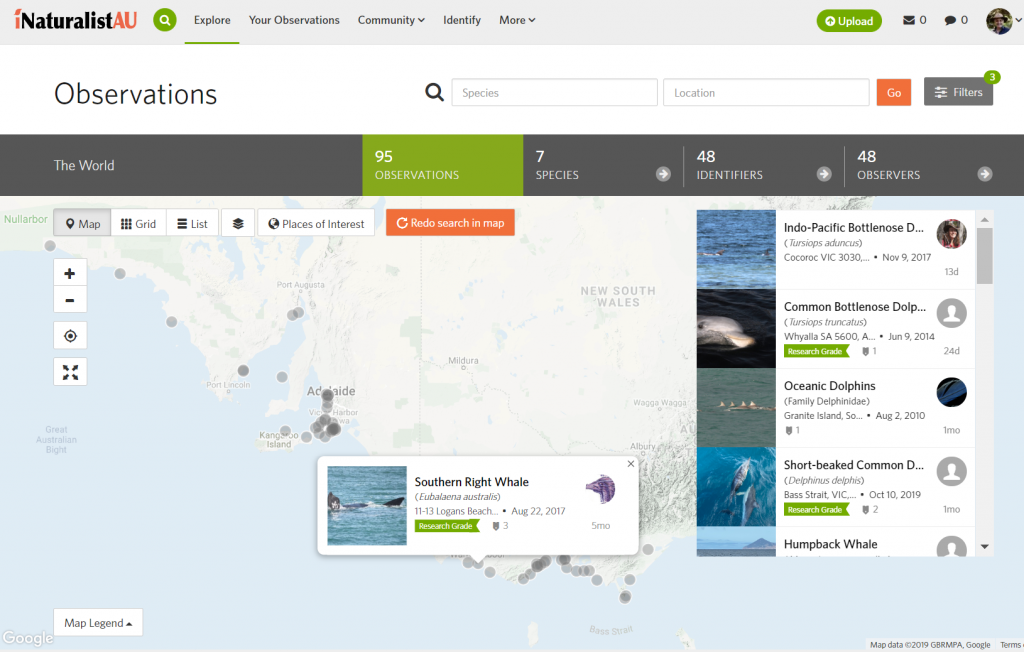

The second is a new partnership between the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) and iNaturalist, the world’s leading global social biodiversity network.

Last month the ALA launched iNaturalist Australia, the Australian node of iNaturalist. It can be used to record individual plant, animal and fungi sightings and thereby access identification specialists who examine your associated images to verify your identification.

While the ALA will be phasing out some of their existing functionality as a result of this iNaturalist partnership (eg. their Record a Sighting function), their BioCollect program continues, with a renewed focus on project-based surveys for environmental and citizen scientists.

To summarise, Glide apps are easy enough to set up and configure to capture any number of fields, data types and media. The data and media are stored in the Google Drive cloud in a readily-accessible CSV format. They are free at the first tier, and fairly inexpensive even at the Pro level for a yearly fee. The apps can be freely distributed and used by project volunteers. Direct geolocation of observations is not currently supported, but addresses can be captured and represented on maps.

iNaturalist and the ALA provide a solid backend infrastructure for setting up projects and linking them into their core datasets for names, taxa, images and user records. The project setup is simple enough, and users can opt in via the free iNaturalist app. Specialists can vet submitted records and images to make the submitted data ‘research grade’. However, the amount of data captured is fixed to a small number of predefined fields such as date, geolocation, species name.

These are both great starting solutions for the many worthy citizen science projects that don’t have reliable funding. We’ve now helped clients set up both Glide apps (eg. for Black Cockatoos) and iNaturalist apps in Australia, which has meant that they can overcome the barrier of ‘the price of entry’ at the very least – and helps with the ‘longevity of data’ somewhat – although I’ll write more about the ‘longevity of data’ in a subsequent post.

While Glide and iNaturalist might work for a range of smaller groups, for those that have more complex research requirements, as well as grants or institutional backing to capture exactly what their project requires, a bespoke citizen science app is still the most valuable tool to quickly capture high-quality research data. We’ve built a range of these over the years, and we’ve had significant success – there are a few interesting initiatives in the app space that we’ll be also discussing soon. In the meantime, we’ll keep looking for more ways that we can support the citizen science community in Australia with ideas and tools like these.

In the meantime, if you’d like to know more about how we can help you with developing a citizen science program, setting up these simple Glide or iNaturalist apps, or how a bespoke smartphone app could even more effectively improve your community engagement and scientific data capture, then please leave a comment below, connect with us on Twitter, LinkedIn or Facebook, or email me directly via alex.chapman@archive.gaiaresources.com.au.

Alex

Comments are closed.